Given their potential to revolutionize many aspects of legal practice and intellectual property, artificial intelligence (“AI”) tools have become a mainstay in the legal space. While AI has its benefits, it also carries unknowns for practitioners and businesses. Imagine this. After the painstaking time and expense of prosecution, you have finally obtained a patent covering your company’s lead product and now seek to enforce your rights to exclude a new competitor. During litigation, the competitor asserts that your patent is invalid as obvious in light of an reference that was generated entirely by artificial intelligence. Should this potentially invalidating reference, which is devoid of any human input, qualify as prior art?

Recognizing that the “increasing power and deployment of AI has the potential to provide tremendous societal and economic benefit and foster a new wave of innovation and creativity,” AI also stands to fundamentally challenge and disrupt our current patent law paradigm.1 Thus, the United States Patent and Trademark Office (“USPTO”) has been busy engaging the community and AI experts alike—launching an AI/ET partnership that to date has hosted 14 events2, issued multiple reports,3 published several guidances,4 and sought comments from the public5 —to tackle both the challenges and opportunities ahead.6

In its most recently issued Request for Comment Regarding the Impact of the Proliferation of Artificial Intelligence on Prior Art, the Knowledge of a Person Having Ordinary Skill in the Art, and Determinations of Patentability Made in View of the Foregoing (“RFC”), two issues were raised concerning the impact of AI on (i) prior art7 and (ii) the knowledge of a person having ordinary skill in the art (“POSA”).8 Both of these issues have the potential to impact the patent validity analysis. For example, AI is capable of generating disclosures that may qualify as prior art, thus increasing the universe of potentially invalidating prior art. Moreover, if a POSA is assumed to have access to AI this will likely have an expansive effect on the POSA’s level of skill and thus influence the obviousness, written description, and enablement analyses, which are conducted from the perspective of a POSA. A POSA’s access to AI may increase their level of skill to such an extent that claims that would have been non-obvious or invalid for lack of written description or enablement are now obvious, adequately described, and enabled. This article provides a brief overview of these issues and posits potential solutions for patent practitioners and policy makers.

The RFC brings forth several considerations regarding the impact AI may have on prior art. For example, “AI may be used to create vast numbers of disclosures that may have been generated without any human contribution, supervision, or review.”9 Should these AI-generated disclosures, which may be devoid of any human input, qualify as prior art that can potentially preclude the patenting of human-created inventions? Given their broad applications and expansive capabilities, AI tools have great potential to further technological advancement. Treating AI-generated disclosures as prior art, however, may disincentivize human innovation by potentially increasing the universe of prior art and thereby increasing the chances of a patent being invalidated.

This issue further begs the question of whether the presumption regarding a POSA’s knowledge of “the relevant art at the relevant time”10 needs to be tailored to account for AI-generated disclosures. Given that AI is capable of “hallucinating” and generating incorrect information,11 coupled with the sheer number of AI-generated disclosures that may never have been viewed by a human, let alone another POSA, some modification of this general presumption is likely warranted. One potential approach, beyond simply excluding AI-generated disclosures, involves imposing further restrictions on AI-generated disclosures that are proffered as prior art. For example, in order for an AI-generated disclosure to qualify as prior art it must have been substantiated by the relevant community. The means by which AI-generated disclosures are published may also be a consideration in determining prior art status. The sheer volume of AI-generated art may even detract from its public accessibility and weigh in favor of precluding AI-generated disclosures from qualifying as prior art, at least in fields where the volume of AI-generated disclosures is particularly high.12

The RFC touches upon other presumptions that may also warrant tailoring in light of AI-generated disclosures. For example, when a prior art reference “expressly anticipates or makes obvious all of the elements of the claimed invention, the reference is presumed to be operable” and the burden is on the applicant to rebut the presumption of operability.13 Put differently, a public disclosure is presumed to provide a description that enables the public to make and use it. Since AI-generated disclosures may never involve human input, review, or testing, they may not deserve this presumption, especially because it could open applicants up to the significant burden of proving the inoperability of a potentially vast number of disclosures. On the other hand, AI-generated disclosures that are premised on fundamental, predictable principles or have been corroborated in some manner by human disclosures may warrant application of the presumption. One must also keep in mind that, “[e]ven if a reference discloses an inoperative device, it is prior art for all that it teaches.”14

Separate and distinct from the issue of AI-generated prior art is the potential impact of AI-tools on the knowledge of a POSA. Whether or not a patent claim is invalid for obviousness, lack of enablement, or lack of written description is determined from the perspective of a POSA at the relevant time.15 The Federal Circuit has identified several factors to consider when determining a POSA’s level of skill based on the context of the instant case, including “(1) the educational level of the inventor; (2) type of problems encountered in the art; (3) prior art solutions to those problems; (4) rapidity with which innovations are made; (5) sophistication of the technology; and (6) educational level of active workers in the field.”16 As the RFC recognizes, AI is a powerful tool that is becoming increasingly available to POSA’s and thus has the potential to influence a POSA’s level of skill.

To what extent, if at all, AI should influence the determination of a POSA’s level of skill warrants careful consideration, especially given the somewhat amorphous capabilities of AI. Given the increasing functionality of AI tools, assuming that a POSA, at the time of the invention, has access to AI can significantly expand the POSA’s hypothetical level of knowledge and consequently have sweeping effects on the validity of claims.

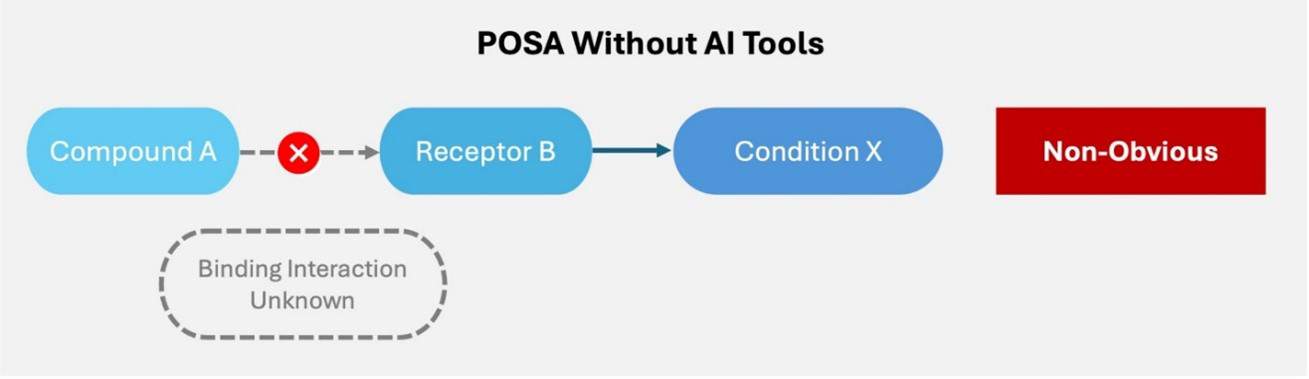

For example, imagine a pharmaceutical method of treatment claim that covers treating Condition X with a chemical compound known as Compound A.

One prior art reference discloses Compound A among a large genus of compounds, and another prior art reference discloses the structure of a biological receptor, known as Receptor B, that plays a critical role in Condition X. Nothing in the prior art indicates or even suggests that Compound A can bind to Receptor B, but this interaction does in fact occur in a manner conducive to treating Condition X. Given the lack of information regarding Compound A binding to Receptor B, the use of Compound A to treat Condition X is likely non-obvious.

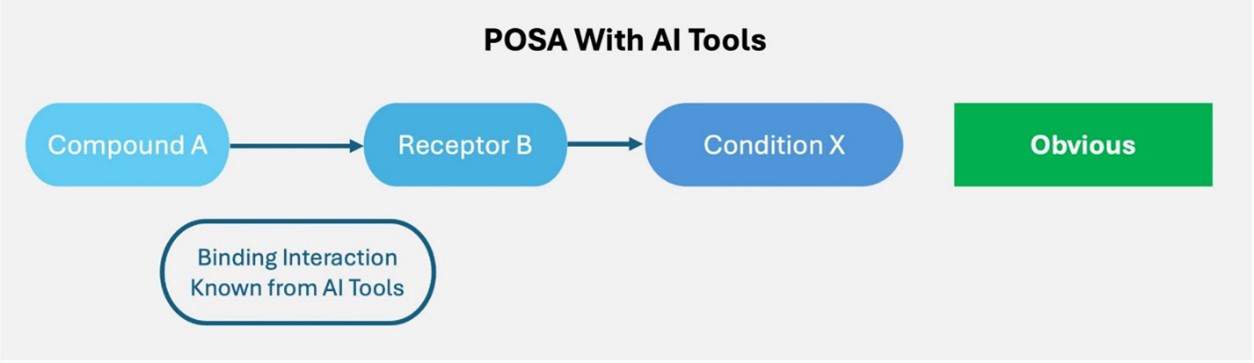

Now consider the same scenario where a POSA at the time of the invention would have had access to high-throughput AI platforms that were developed to identify drug-target combinations, like that of Compound A and Receptor B, based on the structure and binding interactions between chemical compounds and proteins.17 Here, it is possible that a POSA could have used this AI tool to understand the binding interaction.

Thus, a POSA’s access to this type of AI tool has the potential to render obvious the claimed method of treatment where it might not have been obvious without the use of the AI tool.

One potential approach to determining whether a POSA’s access to AI renders a given claim obvious focuses on the particular strategy, or prompting, employed by the AI tool and whether a POSA would have followed the same path. In other words, patent challengers would have to demonstrate that a POSA would have a “motivation to prompt” the AI in way that lead to the claimed invention. This approach, however, does not account for the availability of many different AI tools and the lack of homogeneity or standardization among them, which is discussed further below.

In addition to obviousness, enablement and written description are also determined from the point of view of a POSA. Thus, AI’s potentially expansive impact on a POSA’s level of skill could also influence the enablement and written description analysis, which are often in tension with obviousness. For example, AI’s ability to simulate and predict the results of a myriad of experiments in silico, or performed on a computer, begs the question of whether the Court’s finding of non-enablement in Amgen Inc. v. Sanofi would stand if a POSA was presumed to have access to AI tools.18

In Amgen, the Court found claims directed to a genus of antibodies having a particular function lacked enablement, at least in part, because the patent disclosure left scientists “to engage in ‘painstaking experimentation’ to see what works.”19 But would the amount of experimentation needed to make and use the invention of Amgen have reached the level of undue experimentation if the scientists had AI tools capable of identifying the antibodies that satisfied the functional elements of the claims at issue with minimal real-world experimentation? As explained above, this type of AI tool (i.e. high-throughput AI tool) is already a reality.20

What is particularly concerning with respect to the impact of AI on a POSA’s level of skill is the lack of homogeneity, standardization, and predictability across AI platforms.21 With the number and availability of AI tools rapidly increasing, it is important to keep in mind that each platform is presumably different with different learning models and access to information, and thus may provide varying results. In other words, which, if any, AI tools are a POSA assumed to have access to?

One potential approach is to analyze a POSA’s level of skill based on the AI tools utilized by the inventors, if known, or those frequently utilized in the relevant scientific field. But this approach does not account for the data needed to train many AI tools, such as machine-learning platforms, which includes neural networks and deep-learning tools. At a high level, machine-learning platforms are AI platforms trained to recognize patterns and predict outcomes based on labeled datasets that are provided by the user.22 If a machine-learning platform is fed different data it is likely to provide different results. Is a POSA presumed to have fed the same data into the machine-learning platform as the inventor? This inquiry is complicated by the fact that the data used to teach machine-learning platforms is often confidential. Moreover, some companies have developed proprietary AI tools that may not be available to the public, suggesting that a POSA should not be assumed to have access to proprietary AI tools.

In sum, determining the impact AI tools may have on a POSA’s level of skill is an exceedingly tall order, at least to the extent necessary to enable incorporation into an obviousness analysis, given the complexity and potentially limitless possibilities associated with these platforms.

While AI provides constantly expanding tools with great potentially to further technological development, it carries with it a wide array of practical considerations. Squaring the use and regulation of AI tools with the constitutional imperative “[t]o promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts”23 will require careful consideration to preserve the viability of the patent system and maximize innovation.

777 South Flagler Drive

Phillips Point East Tower, Suite 1000

West Palm Beach, FL 33401