In Mylan Pharm. Inc. v. Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., the Federal Circuit considered whether prior disclosure of a genus of compounds and their pharmaceutically acceptable salts was sufficient to anticipate, under 35 U.S.C. §102, a claim directed to a species of a specific salt of a specific compound having a specific stoichiometric ratio.1 The Court (Judges Lourie, Reyna, and Stoll) upheld the validity of the asserted claims over Merck’s own prior art describing 33 specific compounds and 8 preferred pharmaceutically acceptable salts with various stoichiometric ratios that can be formed for each of the compounds, resulting in 957 different possible salts. Essentially, the Federal Circuit distinguished this case from In re Petering 2 because the prior art disclosure of 957 compounds was a “far cry” from the 20 compounds that were “at once envisaged” by the limited genus in In re Petering.

The patent at issue – Merck’s ’708 patent

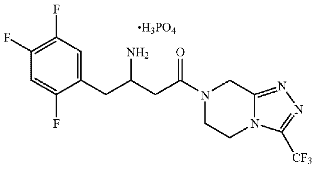

Merck’s U.S. Patent No. 7,326,708 (“the ’708 patent”) is directed to a 1:1 salt form of sitaliptin dihydrogenphosphate (sitagliptin DHP), which is a class of dipeptidyl peptidase-IV (DPP-IV) inhibitors that are used for treating non-insulin-dependent (i.e., Type 2) diabetes. The ’708 patent is listed in FDA’s Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations (the “Orange Book”) for Merck’s Januvia (sitagliptin) and Janumet (sitagliptin + metformin) products.

Claim 1 of the ’708 patent is the sole independent claim and is reproduced below:

(I)

or a hydrate thereof.

Claims 2 and 3 are directed to the (R)- and (S)-configurations, respectively, and claim 4 is directed to a crystalline monohydrate salt of the (R)-configuration, which is the marketed form.3

Prior art reference relied upon by Mylan

Prior to filing of the ’708 patent, Merck filed an earlier PCT application, WO 03/004498 (WO ’498) that discloses a genus of DPP-IV inhibitors, 33 specific compounds that fall within the genus, including the chemical structure for (R)-sitaliptin. WO ‘498 also disclosed “pharmaceutically acceptable salts” of those compounds described therein, including a preferred embodiment for salts formed using “citric, hydrobromic, hydrochloric, maleic, phosphoric, sulfuric, fumaric, and tartaric acids,” but does not disclose the monobasic dihydrogen-phosphate (DHP) salt of sitagliptin as required by the claims of the ’708 patent.4

Lack of Anticipation

Mylan argued that WO ’498 expressly taught the phosphoric acid salt of sitagliptin, by pointing to a disclosure of the chemical structure of (R)-sitagliptin and “pharmaceutically acceptable salts thereof”, and a description of phosphoric acid being the preferred salt in the specification.5 Mylan also argued that WO ’498 specifically describes a 1:1 hydrochloride salt of sitagliptin and that sitagliptin would inherently form a 1:1 salt with DHP.6 Mylan further argued that if the Board finds that WO ’498 teaches the (R)-isomer of sitagliptin phosphate (1:1), then a person of ordinary skill in the art (“POSA”) would “at once envisage” (S)-sitagliptin phosphate (as recited in claim 3) because it is the only other possible isomer.7

The “at once envisage” language stems from In re Petering where the Court found that a POSA could at once envisage each member of a limited class that contained 20 compounds.8 Mylan also attempted to persuade the Board that the primary list of 33 compounds and secondary list of 8 salts together form a single list of different combinations of compounds and their preferred salts. Mylan argued that lists are often treated differently under Federal Circuit case law because a compound included in a list can anticipate whereas a genus cannot always anticipate a later species claim.9

The Board was not convinced and stated that WO ’498 does not expressly describe or exemplify any specific phosphate salt of sitagliptin (or any phosphate of any compounds), let alone a 1:1 sitagliptin DHP salt.10 Although WO ’498 provides a list of 33 compounds that includes sitagliptin, and a list of 8 preferred salts that includes phosphoric acid, there is no single list that expressly includes all the preferred salts for each and every one of the listed 33 compounds. Furthermore, the Board sided with Merck’s expert who provided an unrebutted opinion that WO ’498 discloses about 957 different salts, which is not so narrow such that a POSA could at once envisage and, therefore, anticipate a claim directed to a 1:1 sitagliptin DHP salt.

Mylan also argued that a 1:1 sitagliptin DHP salt was inherent and formed “every time” based on testimony of its own expert who testified that a 1:1 salt was the only possible salt of sitagliptin.11 Mylan relied on the disclosure of a 1:1 hydrochloride salt of sitagliptin in Example 7 of WO ’498 and extended the same stoichiometric ratio to a phosphate salt of sitagliptin. However, the Board was not persuaded by Mylan’s expert and concluded that that a POSA would not simply conclude that whatever applies for reacting hydrochloric acid and sitagliptin also applies to reacting phosphoric acid and sitagliptin because there are several chemical differences between these two acids.12 Rather, evidence in the record showed that mixing sitagliptin and phosphoric acid led to other ratios including 1:2, 2:1, and 3:2 salts of sitagliptin : DHP.13 Thus, the Board found Mylan’s inherent anticipation argument unpersuasive.14

Furthermore, as a result of the Board finding that WO ’498 did not disclose the (R)-isomer of sitagliptin DHP (1:1), Mylan’s contingent argument that a POSA would at once envisage (S)-sitagliptin DHP (as in claim 3) also lacked merit.15

Lack of obviousness

Mylan also argued that certain claims of the ’708 patent were obvious over WO ’498, either alone or in combination with Bastin and/or Brittain.16

Merck successfully showed that they reduced to practice the invention of claims 1, 2, 17, 19, and 21–23 of the ’708 patent prior to the publication of WO ’498.20 As such, WO ’498 did not qualify as prior art under 35 U.S.C. §102(a) for these claims but only as prior art under 35 U.S.C. §102(e).21 Under the exception provided by pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. §103(c)(1), Merck was able to remove WO ’498 as prior art for invalidity under 35 U.S.C. §103 against the above mentioned claims by showing common ownership between WO ’498 and the ’708 patent at the time the invention was made.22

Regarding claim 3 of the ’708 patent, directed to the (S)-isomer of sitagliptin DHP (1:1), the Board found Mylan’s arguments unpersuasive. Mylan’s argument that claim 3 was obvious over WO ’498 alone was predicated on the Board’s finding that WO ’498 discloses the (R)-isomer of sitagliptin DHP (1:1). As the Board did not find the (R)-isomer of sitagliptin DHP (1:1) was disclosed in WO ’498, they dismissed this argument.23

The Board also dismissed Mylan’s argument that the combination of WO ’498 and Bastin would motivate a POSA to make the 1:1 (S)-sitagliptin and render obvious claim 3 because neither WO ’498 nor Bastin disclose any (S)-isomers or racemates of any sitagliptin salt.24 The Board noted that Mylan set forth no benefit of the (S)-isomer of 1:1 sitagliptin DHP, especially when evidence on the record suggests that making the salts are highly unpredictable.25

Claim 4 of the ’708 patent is directed to the crystalline monohydrate form of the (R)-isomer. Mylan argued that WO ’498 in combination with Bastin and Brittain would render claim 4 obvious. However, the Board found Mylan’s arguments unpersuasive.26 The Board stated that Mylan failed to articulate why a POSA would be motivated to pursue a crystalline monohydrate form of 1:1 sitagliptin DHP, especially when the evidence on record discourages a POSA from doing so in view of known problems with hydrates, such as instability and low solubility, and the unpredictable nature of making hydrates.27 Furthermore, the Board was persuaded by objective evidence of nonobviousness offered by Merck on thermal stability, reduced sticking, and reduced discoloration of the monohydrate form of 1:1 sitagliptin DHP in pharmaceutical formulations as compared to other hydrated salts of sitagliptin.28

Mylan made three arguments on appeal, that the Board erred in (1) their determination of no anticipation by WO ’498, (2) that the ’708 patent antedates WO ’498, and (3) claims 3 and 4 of the ’708 patent were not obvious.29

Affirming Lack of Anticipation

The Federal Circuit agreed with the Board’s decision that WO ’498 did not expressly disclose 1:1 sitagliptin DHP. The Court relied on Mylan’s expert who testified that nothing in WO ’498 directs a POSA to sitagliptin from among the 33 compounds, or to a phosphate salt among the preferred 8 salts.30 The Court also agreed with the Board that WO ’498 does not inherently disclose 1:1 sitagliptin DHP because the combination of the 33 compounds and the 8 preferred pharmaceutically acceptable salts (with various stoichiometric ratios) results in 957 salts that cannot individually be “at once envisage[d],” in contrast to the 20 compounds “envisaged” by the narrow limited genus in Petering. However, the Court would not provide a bright line threshold, e.g., a specific number, for defining a “limited class” as it depends on the facts defining the class itself.31

Affirming Lack of Obviousness

The Court also agreed with the Board’s decision that Merck’s invention antedated WO ’498. The Court found that there was substantial laboratory evidence that Merck developed the 1:1 sitagliptin DHP prior to publication of WO ’498.32 As such, WO ’498 is only eligible as prior art under pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. § 102(e), which can be disqualified as prior art pursuant to pre-AIA § 103(c). The Federal Circuit agreed that Merck owned both WO ’498 and the ’708 patent at the time the invention was made and therefore WO ’498 was not qualified as prior art under pre-AIA § 103.33

Regarding claim 3 (directed to the (S)-isomer of 1:1 sitagliptin DHP), the Court agreed with the Board that Mylan failed to advance any expected or theoretical benefit for making the (S)-isomer and that the general disclosure of isomers in WO ’498 encompasses millions of compounds with no motivation to make the (S)-isomer of sitagliptin with a reasonable expectation of success.34 The Court also credited Merck’s argument that Bastin lacks a specific motivation, such as a screening or optimization protocol, that when combined with WO ’498 would lead to the (S)-isomer, or even a racemic mixture, of sitagliptin.

As to claim 4 (directed to the crystalline monohydrate form of (R)-sitagliptin DHP), the Court agreed with the Board that there was no motivation to combine WO ’498 with Bastin and Brittain, and that a POSA would have no reasonable expectation of success in making the combination.35 The Court was persuaded by testimony from Mylan’s expert that a POSA could not predict with any degree of certainty that a hydrate can form, and from Merck’s expert that a POSA would have sought to avoid hydrates and that forming salts/hydrates is highly unpredictable.36 The Court also noted that a POSA would avoid making hydrates due to solubility and stability challenges during the drug-production process, and that the monohydrate has unexpectedly favorable properties and satisfies the objective indicia of nonobviousness, which undermines Mylan’s challenge to claim 4.37

Although the Federal Circuit affirmed that a genus encompassing 957 different compounds does not anticipate a later filed species claim, the Court declined to provide a bright line rule as to how many species within a genus would be considered sufficiently limited such that each individual compound encompassed by the genus can be “at once envisage” by a POSA. It remains that any potential prior art effect of an earlier genus disclosure on a subsequently file patent claim directed to a specific species will depend on an overall factual analysis.

Furthermore, even if an earlier genus disclosure is not considered anticipatory of a later patent claim directed to a species, the earlier genus disclosure may still be relied upon as a basis for obviousness. Here, the ’708 patent was filed pre-AIA. Merck was, therefore, able to rely on evidence of earlier reduction to practice in December 2001 to antedate WO ’498 and disqualify it as prior art for obviousness purposes.

Had post-AIA laws applied, Merck would not have been able to remove WO ’498 as prior art for obviousness purposes by simply demonstrating common ownership of the two inventions. WO ’498, which published on January 16, 2003 before the priority date of June 24, 2003 for the ’708 patent, would be considered prior art under 35 U.S.C. § 102(a)(1) had post-AIA laws applied. Prior art under §102(a)(1) can only be removed if it was published less than 1 year before the effective filing date of a later patent filing pursuant to §102(b)(1)(A) or §102(b)(1)(B). The option under §102(b)(1)(B) requires a demonstration that the subject matter of the earlier disclosure was publicly disclosed earlier by the inventor(s) of the ’708 patent, which does not appear to be applicable based on the facts of this case. The only remaining option would be under §102(b)(1)(A), which requires demonstrating that the earlier disclosure was derived from at least one of the inventors of the ’708 patent, which is significantly more onerous than simply demonstrating common ownership. As patent drafters continue to operate under post-AIA laws, it may be helpful to revisit prior genus patent applications and consider their potential prior art effect before the genus patent applications are published.

777 South Flagler Drive

Phillips Point East Tower, Suite 1000

West Palm Beach, FL 33401