In the 1950’s, Alan Turing famously asked, “Can machines think?”1 Decades later, artificial intelligence—a term coined after Turing’s death—has become a facet of our everyday lives. Artificial Intelligence (AI) can be used to improve efficiency, predict outcomes with a high degree of accuracy, and even create new data and solutions. At the same time, AI and its capabilities are evolving more quickly than the laws and regulations governing its use. As of today, AI is “inventing” new materials and manufacturing processes, and is used throughout the drug discovery process, including the creation of the world’s first AI-designed anti-fibrotic small molecule inhibitor drug (i.e. INS018_055) now being tested in human patients in the U.S. and China.2 Generative AI, in particular, presents new challenges in intellectual property law—from inventorship issues to liability. Just this month, Google updated its Terms of Service, effective May 22, 2024, to state that Google will not claim ownership of AI-generated content.3 This update reflects a broader industry trend aimed at addressing user concerns about data privacy and intellectual property rights in the context of AI-generated material.4 As AI systems threaten not just to augment, but replace human ingenuity in the creative and inventive processes, should AI’s inventive contributions be afforded legal protection with which human ingenuity is rewarded?

We previously examined the intersection of AI and copyright law, focusing on the Thaler v. Perlmutter decision, which held that a work of art created by AI is not eligible for copyright registration because it lacks human authorship.5 Here, we focus on similar issues that have surfaced in patent law, particularly with respect to inventorship in AI-assisted patent applications (meaning patent applications generated using AI). We will discuss recent guidance from the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) and dive into questions that the field is just beginning to consider as the number of AI-assisted patent applications and AI-assisted inventions has risen in recent years, making AI an increasingly important topic in patent law.6 According to a report published in October 2020 by the Office of the Chief Economist of the USPTO, the number of AI-assisted patent applications from 2002 to 2018 increased from 30,000 to more than 60,000 annually.7 This report, which traced the volume, nature, and evolution of AI contained in U.S. patents and patent applications, was itself prepared using AI.8

The use of AI in innovation has raised questions such as whether an AI system can be an inventor and whether there are subject matter eligibility issues unique to AI inventions.9 The ultimate goal of patent law is to incentivize and reward innovation in exchange for public disclosure of an invention.10 U.S. courts, the USPTO, and lawmakers are challenged with promoting developments in AI while maintaining the integrity of the patent system. Here, we discuss the intersection of AI and patent law, including inventorship issues in AI-assisted patents and patent applications and the impact of AI on the pharmaceutical industry.

In 2022, the Federal Circuit first decided whether an AI software system can be listed as an inventor on a patent application in Thaler v. Vidal.11 Stephen Thaler filed two patent applications in 2019 naming the AI software system that generated the claimed invention as the sole inventor, and assigned the rights to himself.12 The USPTO denied Thaler’s applications because they failed to list a valid inventor, and Thaler challenged the USPTO’s conclusion in the District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia.13 The district court granted the USPTO’s motion for summary judgment, holding that inventors listed on patent applications must be natural persons.14 The Federal Circuit affirmed, finding that the Patent Act provides that an inventor, including a joint inventor or coinventor, is an “individual,” which the Supreme Court has held refers to a human being.15 However, the Federal Circuit was “not confronted. . . with the question of whether inventions made by human beings with the assistance of AI are eligible for patent protection.”16

Discussions regarding inventorship and AI-assisted inventions have continued to evolve since Thaler. On October 30, 2023, President Biden issued an “Executive Order on the Safe, Secure, and Trustworthy Development and Use of Artificial Intelligence,” which set out eight guiding policies and principles to govern the development and use of AI to which relevant agencies must adhere.17 Recognizing the need to tackle “novel intellectual property (IP) questions and other problems to protect inventors and creators,” the Executive Order directed the USPTO to issue guidance to USPTO patent examiners and applicants addressing inventorship and the use of AI within 120 days of the order.18 The Executive Order further instructed the USPTO to issue guidance within 270 days addressing other considerations at the intersection of AI and IP as the USPTO deems necessary, including guidance on patent eligibility.19

On February 13, 2024, the USPTO published the first set of guidance on the Federal Register providing clarity on how the USPTO will analyze inventorship issues as AI systems play an increasing role in the innovation process, and requested public comment on or before May 13, 2024.20 Citing Thaler, the guidance states that while inventorship on U.S. patents and patent applications is limited to natural persons, AI-assisted inventions are not categorically unpatentable if natural persons significantly contributed to the claimed invention.21 The guidance emphasizes that the touchstone of inventorship is conception, which is an act performed in the mind that can only be attributed to natural persons.22 To that end, the guidance focuses on what constitutes a significant contribution by a natural person and offers a non-exhaustive list of principles to assist applicants and USPTO personnel in determining proper inventorship.23

The guidance instructs that a natural person named as an inventor for AI-assisted inventions must contribute in a significant manner as determined by the factors articulated in Pannu v. Iolab Corporation.24 The Patent Act requires each claim of a patent or patent application to be invented by at least one named inventor.25 Thus, when a natural person uses an AI system to create an invention, that person must make a significant contribution to every claim of the patent for inventorship to be proper.26 This is especially vital to pharmaceutical innovators as AI becomes integral to the drug discovery and development process.

Recognizing that there is no bright-line test, the USPTO set forth five guiding principles to help applicants determine whether an inventor’s contribution is significant.27 These below five principles incorporate the USPTO’s policy objective “to encourage human ingenuity.”28

Not only is generative AI useful for inventors, it can improve efficiency and lower the cost of practicing before the USPTO for practitioners, parties, and examiners alike.29 Patent examiners are performing AI-enabled prior art searches and, at the same time, practitioners are using AI-based tools to research prior art and automate the patent review and application processes.30 Recognizing that the use of AI-based tools in legal proceedings presents risks, the USPTO issued a second guidance on April 11, 2024, pursuant to the October 2023 Executive Order to remind practitioners of the agency’s rules and policies and to suggest ways to mitigate risks associated with the use of AI systems in matters before the USPTO.31

This second guidance emphasizes that there is no prohibition against using generative AI tools in drafting documents for submission to the USPTO, nor is there an obligation to disclose that such tools were used.32 Nonetheless, practitioners and applicants must be aware of USPTO policies and duties, and how they apply in the context of AI.33

With respect to inventorship, although there is no per se requirement to notify the USPTO that an AI system was used in the inventive process, in some circumstances applicants must submit this information to satisfy their duty of disclosure.34 As the guidance explains, the use of an AI tool must be disclosed to the USPTO if it is material to patentability.35 For example, the duty of disclosure requires an applicant to submit evidence that a named inventor did not significantly contribute to an invention that was created primarily through AI.36 This could occur if an AI system is used to draft a patent application and introduces an alternative embodiment for which there was no human contribution.37 Therefore, even if AI was only used to prepare an application, practitioners should carefully evaluate the application to ensure that inventorship is proper and the information is characterized correctly and completely.38 Pursuant to the guidance, practitioners and applicants must submit information regarding interaction with an AI system if there is any question as to whether at least one named inventor contributed significantly to an AI-assisted invention.39 As discussed below, an applicant’s decision whether or not to disclose the use of AI in the invention creation process may impact litigation down the line.

Given the increased use of AI and other technologies in the pharmaceutical industry, litigation strategy and forward-thinking is of utmost importance. A hard question that will likely need to be answered by the courts is: What truly constitutes significant human contribution in an AI-assisted patent?40 The answer to this question requires drawing a line between material purely created by AI and material containing patentable human contribution, which will vary by case. Determining which side of the line an invention falls on is a complex issue and will likely play out in litigation over the coming years.

As the number of patented AI-assisted inventions rises, litigants will look for new ways to invalidate AI-assisted patents. One argument litigants may raise is whether there was actually significant human contribution to the patented invention. Litigants will argue that even though the patent was granted, had the examiner understood the minimal extent of human contribution, the application would have been rejected for improper inventorship. Patentees, therefore, must be cognizant of this possible invalidity challenge and preemptively create a record to combat such challenges, regardless of what AI-assistance they disclose to the USPTO.41

One way to create a record is to document all ways in which a human, whether employee or contractor, has made a contribution to the patented invention.42 Specifically, it is important to document any prompting that a human inputted into AI because the USPTO guidance suggests that extensive prompting can be evidence of significant human contribution.43 Creating a record of human contribution to AI inputs and outputs will bolster the fact that the patented invention was not completely created using AI and that a human was involved throughout the process.

Overall, practitioners and applicants must keep in mind that the answer to what constitutes significant human contribution is somewhat subjective. Reasonable minds can therefore differ, which makes the threshold question much more challenging to prove. A complete and thorough record, however, will strengthen a patentee’s argument regarding human contribution and can be persuasive in proving significant human contribution. By thinking about and preparing for litigation from the outset, companies can protect their IP and ensure that they maximize their use of AI.

The USPTO’s guiding principles aim to make the U.S. a rapid and safe adopter of AI in practice while ensuring it is being used in a constructive manner. Keeping this goal in mind, the USPTO created the AI and Emerging Technology (“ET”) Partnership.44 The Partnership is meant to “foster and protect innovation in artificial intelligence and emerging technologies and bring those innovations to impact to enhance our country’s economic prosperity and national security and to solve world problems.”45 The Partnership is the ongoing cooperative effort between the USPTO and the AI/ET community that hosts a series of meetings to explore initiatives at the USPTO and discuss IP policy issues impacting these technologies. Anyone interested in the intersection of AI and IP is encouraged to visit their website, participate in the meetings, and provide feedback to help shape the policies and laws surrounding the use of this technology.

As part of the drug development process, it takes immense time and effort to discover and synthesize small molecules for use in new drug candidates. AI can, and in many cases has, rapidly accelerated research and development for drug discovery. Drug discovery, generally, can cost between 1 to 2 billion46 and up to 2.8 billion47, and often takes between 10 to 15 years to come to market. The early discovery stage—where AI is most often utilized—alone takes an average of 3 to 6 years and accounts for 42% of the total capitalized costs in the development of a new drug.48 Pharmaceutical companies, scientists, and industry stakeholders are motivated to find ways to reduce the immense time and expense (especially given the high failure rate of drugs to market). AI provides both a solution and opportunity. Integrating AI within the drug discovery process is an attractive solution as it is estimated that development time and costs can be reduced by one-third utilizing AI and other computer-assisted tools.49

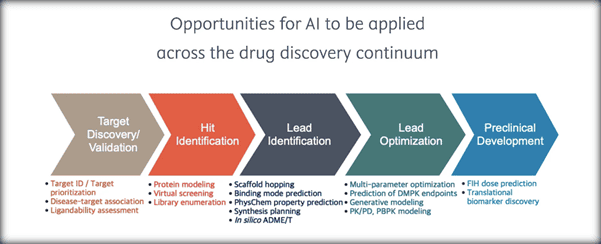

AI, in fact, can be utilized in numerous ways across the drug discovery continuum, as shown below:50

AI has allowed small molecule discovery to evolve from manual testing and assays by chemists to automated and increasingly sophisticated AI techniques capable of predicting and understanding structure-activity relationships, making accurate absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity predictions, accelerating synthesis planning for novel compounds, and improving route optimization for known compounds.51 AI, therefore, can increase speed, lower costs, improve success rates, and boost innovation for the pharmaceutical industry.

Pharmaceutical companies that have incorporated AI into drug development have gained an advantage over competitors not using the same technology. One study found that companies using an “AI-first approach have more than 150 small molecule drugs in discovery and more than 15 already in clinical trials.”52 And AI is opening doors for the development of new drugs for previously untreatable diseases. For example, Stanford Medicine researchers have created a new AI model, SyntheMol, to create recipes for chemists to synthesize in the lab.53 Using this new technology, Stanford has been able to develop potential new drugs for antibiotic-resistant bacteria, diseases that are responsible for nearly 5 million deaths globally a year.54 The continued reliance on and incorporation of AI in the pharmaceutical industry is expected to help create dozens of new medicines and a $50 billion market over the next year.55 It is therefore important for pharmaceutical companies to implement AI in the drug discovery process sooner rather than later, or risk losing out to competitors.

With AI revolutionizing the pharmaceutical industry, companies must closely pay attention to the ever-changing legal landscape to ensure protection of their intellectual property. For many, incorporation of AI into their processes is novel and these companies do not want to risk losing patent protection for new drugs merely because AI was used.

As explained earlier, the main guiding principle in ensuring patentability when using AI is the requirement of active participation by the human inventor that is distinguishable from the operation of the AI system. And just because AI was used does not automatically mean that an invention is unpatentable. While early guidance is still not clear there are many factors for pharmaceutical companies to consider when using AI for drug development. The Inventorship Guidance provided by the USPTO provides several examples for what could be considered “significant contributions” by a human, including: (1) prompting AI to elicit a particular solution to a problem; (2) training AI to answer a question; or (3) designing an experiment based on an AI output.56 This inventorship inquiry is fact-specific and will be decided on a case-by-case basis to determine whether there is “significant contribution” by a natural person.57 This means companies will have to wait until courts determine what meets the standard for such contribution. In the meantime, companies can help protect patentability of new drugs by ensuring they do not solely rely on AI. Rather, companies should use AI as a supplementation and program it for specific tasks as recommended by the USPTO Guidance.

Patent protection may not be the only route for intellectual property protection. Trade secrets offer a means to fill the gaps in patent protection. In particular, trade secrets are intellectual property rights protecting confidential and proprietary information that is commercially valuable, known to only a limited group of persons, for which reasonable steps are taken by the rightful holder of the information to keep it secret.58 Whether to keep something a trade secret or apply for a patent, however, must be decided early on in the drug development cycle. Once a company decides to file for patent protection, disclosure of information that otherwise would have been a trade secret is required and disclosure of this proprietary information will extinguish trade secret rights. Since AI is data driven, there can be an uphill battle to obtain patent protections. Trade secrets are meant to protect innovations relying heavily on data and know-how for which it can be challenging to obtain patent protection. Trade secrets could protect data pertaining to small molecules, algorithms, source codes, chemical processes, and nearly any other kind of valuable information to pharmaceutical companies. And trade secrets, unlike patents, do not have an expiration date meaning companies should carefully consider the appropriate avenue to safeguard their intellectual property.

Advances in AI systems are becoming more important than ever for a company’s continued success. It is thus necessary to keep up with the latest changes in the law, understand emerging industry trends, and engage in best practices to enable companies to maximize the benefits of AI while protecting their intellectual property. The USPTO is actively exploring the intersection of AI and patent law and plans to engage with stakeholders, issuing guidance as appropriate. Updates to the inventorship guidance may follow the public comment period ending on May 13, 2024, and we expect to see further USPTO guidance published in the coming months addressing questions beyond inventorship such as subject matter eligibility, obviousness, and enablement. We encourage you to follow along as we provide regular updates on the intersection of AI and patent law and expand our discussion to other areas of intellectual property law.

777 South Flagler Drive

Phillips Point East Tower, Suite 1000

West Palm Beach, FL 33401